Columbidae is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They feed largely on plant matter, feeding on seeds (granivory), fruit (frugivory), and foliage (folivory).

In colloquial English, the smaller species tend to be called “doves”, and the larger ones “pigeons”,[2] although the distinction is not consistent,[2] and there is no scientific separation between them.[3] Historically, the common names for these birds involve a great deal of variation. The bird most commonly referred to as “pigeon” is the domestic pigeon, descendant of the wild rock dove, which is a common inhabitant of cities as the feral pigeon.

Columbidae contains 51 genera divided into 353 species.[4] The family occurs worldwide, often in close proximity to humans, but the greatest diversity is in the Indomalayan and Australasian realms. 118 species (34%) are at risk,[4] and 13 are extinct,[5] with the most famous examples being the dodo, a large, flightless, island bird, and the passenger pigeon, that once flocked in the billions.

Etymology

Pigeon is a French word that derives from the Latin pīpiō, for a ‘peeping’ chick,[6] while dove is an ultimately Germanic word, possibly referring to the bird’s diving flight.[7] The English dialectal word culver appears to derive from Latin columba.[6] A group of doves has sometimes been called a “dule”, taken from the French word deuil (‘mourning’).[8]

Origin and evolution

Columbiformes is one of the most diverse non-passerine clades of neoavians, and its origins are in the Cretaceous[9] and the result of a rapid diversification at the end of the K-Pg boundary.[10] Whole genome analyses have found Columbiformes is the sister clade to the clade Pteroclimesites a clade consisting the orders Pterocliformes (sandgrouses) and Mesitornithiformes (mesites).[11][12][13] The columbiform-pteroclimesitean clade, or Columbimorphae, monophyly has been supported from several studies.[11][12][14][15][16][17][18][19]

Taxonomy and systematics

See also: List of Columbidae genera and List of Columbidae species

The name ‘Columbidae’ for the family was first used by the English zoologist William Elford Leach in a guide to the contents of the British Museum published in 1819.[20][21] However, Illiger in 1811 established an older name for the family group (“Columbini”) and would actually be the proper authority for Columbidae.[22]

The interrelationships of columbids (between subfamilies) and the ergotaxonomy of them has been debated, with many different interpretations of how they should be classified. As many as five to six families, along with many subfamilies and tribes, have been used in the past including the family Raphidae for the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire.[23][24][25] A 2024 paper on the systematics and nomenclature of the dodo and the solitaire from Young and colleagues also provided an overview of columbid family-group nomina. They recommended recognizing three subfamilies: Columbinae (New World doves and quail-doves, and columbin doves), Claravinae (American ground-doves), and Raphinae (Old World doves and pigeons including the dodo and solitaire).[22] A 2025 paper on the molecular phylogenetic placement of the Cuban endemic blue-headed quail-dove from Oswald and colleagues found the species to be a sister group to Columbinae, as opposed to being a true columbine or a raphine as previous authors have suggested in the past. These authors recommended that the blue-headed quail-dove should be placed in fourth monotypic subfamily, Starnoenadinae.[26]

These taxonomic issues are exacerbated by columbids not being well represented in the fossil record,[27] with no truly primitive forms having been found to date.[citation needed] The genus Gerandia has been described from Early Miocene deposits in France, but while it was long believed to be a pigeon,[28] it is now considered a sandgrouse.[29] Fragmentary remains of a probably “ptilinopine” Early Miocene pigeon were found in the Bannockburn Formation of New Zealand and described as Rupephaps;[29] “Columbina” prattae from roughly contemporary deposits of Florida is nowadays tentatively separated in Arenicolumba, but its distinction from Columbina/Scardafella and related genera needs to be more firmly established (e.g. by cladistic analysis).[30] Apart from that, all other fossils belong to extant genera.[31]

List of genera

Fossil species of uncertain placement:

- Genus †Arenicolumba Steadman, 2008

- Genus †Rupephaps Worthy, Hand, Worthy, Tennyson, & Scofield, 2009 (St. Bathans pigeon, Miocene of New Zealand)

Subfamily Columbinae (typical pigeons and doves) Illiger, 1811

- Tribe Columbini Illiger, 1811

- Genus Patagioenas (American pigeons, 17 species)

- Genus †Ectopistes (passenger pigeon; extinct 1914)

- Genus Reinwardtoena (3 species)

- Genus Turacoena (3 species)

- Genus Macropygia (typical cuckoo-doves, 15 species)

- Genus Streptopelia (turtle doves and collared doves, 13 species)

- Genus †Dysmoropelia Olson, 1975 (Saint Helena dove) (prehistoric)

- Genus Columba (Old World pigeons, 35 species of which 2 recently extinct)

- Genus Spilopelia (2 species)

- Genus Nesoenas (3 species)

- Tribe Zenaidini (quail-doves and allies) Bonaparte, 1853

- Genus Geotrygon (10 species)

- Genus Leptotrygon (olive-backed quail-dove)

- Genus Leptotila (11 species)

- Genus Zenaida (7 species)

- Genus Zentrygon (8 species)

Subfamily Starnoenadinae Bonaparte, 1855

- Genus Starnoenas (blue-headed quail-dove)

Subfamily Claravinae (American ground doves) Todd, 1913

- Genus Claravis (blue ground dove)

- Genus Paraclaravis (2 species)

- Genus Columbina (9 species)

- Genus Metriopelia (4 species)

- Genus Uropelia (long-tailed ground dove)

Subfamily Raphinae (Old World doves and pigeons) Oudemans, 1917 (1835)

- Tribe Phabini (bronzewings and relatives) Bonaparte, 1853

- Genus Gallicolumba (bleeding-hearts and allies, 7 species)

- Genus Henicophaps (2 species)

- Genus Pampusana (13 species of which 3 recently extinct)

- Genus Ocyphaps (crested pigeon)

- Genus Petrophassa (rock pigeons, 2 species)

- Genus Leucosarcia (wonga pigeon)

- Genus Geopelia (5 species)

- Genus Phaps (Australian bronzewings, 3 species)

- Genus Geophaps (3 species)

- Tribe Ptilinopini (fruit doves and imperial pigeons) Selby, 1835

- Genus ?†Tongoenas Steadman & Takano, 2020 (Tongan giant pigeon) (prehistoric)

- Genus Phapitreron (brown doves, 3 species)

- Genus Ducula (imperial pigeons, 42 species)

- Genus Ptilinopus (fruit doves, around 50 living species, 1–2 recently extinct)

- Genus Alectroenas (blue pigeons, 3 living species, 3-4 recently extinct)

- Genus Drepanoptila (cloven-feathered dove)

- Genus Hemiphaga (2 species)

- Genus Cryptophaps (sombre pigeon)

- Genus Lopholaimus (topknot pigeon)

- Genus Gymnophaps (mountain pigeons, 4 species)

- Tribe Raphini Oudemans, 1917 (1835)

- Genus ?†Natunaornis (Viti Levu giant pigeon) (prehistoric)

- Genus Trugon (thick-billed ground pigeon)

- Genus †Microgoura (Choiseul crested pigeon, extinct early 20th century)

- Genus Otidiphaps (pheasant pigeon)

- Genus Goura (crowned pigeons, 4 species)

- Genus Didunculus (tooth-billed pigeon)

- Genus ?†Deliaphaps De Pietri, Scofield, Tennyson, Hand, & Worthy, 2017 (Zealandian dove, Miocene of New Zealand)

- Genus Caloenas (Nicobar pigeon)

- Genus †Bountyphaps Worthy & Wragg, 2008 (Henderson Island pigeon) (prehistoric)

- Subtribe Raphina (Dodo and solitaire) Oudemans, 1917 (1835)

- Genus †Raphus (dodo, extinct late 17th century)

- Genus †Pezophaps (Rodrigues solitaire, extinct c. 1730)

- Tribe Treronini Gray, 1840 (1836)

- Genus Treron (green pigeons, 30 species)

- Tribe Turturini Gray, 1840

- Genus Oena (Namaqua dove, tentatively placed here)

- Genus Turtur (wood doves, 5 species; tentatively placed here)

- Genus Chalcophaps (emerald doves, 3 species)

Description

Anatomy and physiology

Overall, the anatomy of Columbidae is characterized by short legs, short bills with a fleshy cere, and small heads on large, compact bodies.[32] Like some other birds, the Columbidae have no gall bladders.[33] Some medieval naturalists concluded they have no bile (gall), which in the medieval theory of the four humours explained the allegedly sweet disposition of doves.[34] In fact, however, they do have bile (as Aristotle had earlier realized), which is secreted directly into the gut.[35]

The wings of most species are large, and have eleven primary feathers;[36] pigeons have strong wing muscles (wing muscles comprise 31–44% of their body weight[37]) and are among the strongest fliers of all birds.[36]

In a series of experiments in 1975 by Dr. Mark B. Friedman, using doves, their characteristic head bobbing was shown to be due to their natural desire to keep their vision constant.[38] It was shown yet again in a 1978 experiment by Dr. Barrie J. Frost, in which pigeons were placed on treadmills; it was observed that they did not bob their heads, as their surroundings were constant.[39]

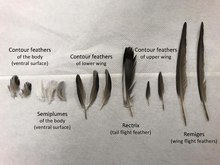

Feathers

Columbidae have unique body feathers, with the shaft being generally broad, strong, and flattened, tapering to a fine point, abruptly.[36] In general, the aftershaft is absent; however, small ones on some tail and wing feathers may be present.[40] Body feathers have very dense, fluffy bases, are attached loosely into the skin, and drop out easily.[41] Possibly serving as a predator avoidance mechanism,[42] large numbers of feathers fall out in the attacker’s mouth if the bird is snatched, facilitating the bird’s escape. The plumage of the family is variable.[43]

Granivorous species tend to have dull plumage, with a few exceptions, whereas the frugivorous species have brightly coloured plumage.[44] The genera Chalcophaps, Ptilinopus and Alectroenas include some of the most brightly coloured pigeons. Pigeons and doves may be sexually monochromatic or dichromatic.[45] In addition to bright colours, some pigeon species may have crests or other ornamentation.[46]

Flight

Many Columbidae are excellent fliers due to the lift provided by their large wings, which results in low wing loading;[47] They are highly maneuverable in flight[48] and have a low aspect ratio due to the width of their wings, allowing for quick flight launches and ability to escape from predators, but at a high energy cost.[49] A few species are long-distance migrants, with some populations of the European turtle dove migrating in excess of 5,000 km between northern Europe in summer and tropical Africa in winter, and the Oriental turtle dove nearly as far in eastern Asia between eastern Siberia and southern China.

Size

Pigeons and doves exhibit considerable variation in size, ranging in length from 15 to 75 centimetres (5.9 to 29.5 in), and in weight from 30 g (0.066 lb) to above 2,000 g (4.4 lb).[50] The largest extant species are the crowned pigeons of New Guinea,[51] which are nearly turkey-sized, with lengths of 66–79 cm (2.17–2.59 ft) and weights ranging 1.8–4 kg (4.0–8.8 lb).[52][53][54] One of the largest arboreal species, the Marquesan imperial pigeon with a length of 55 cm (22 in), currently battles extinction.[55][56] The extinct, flightless dodo is the largest columbid to have ever existed, with a height of about 62.6–75 cm (24.6–29.5 in), and a range of suggested weights from 10.2–27.8 kilograms (22–61 lb), although the higher estimates are thought to be based on overweight birds.[57][58][59][60]

The least massive columbids belong to species in the genus Columbina; the common ground dove (Columbina passerina) and the plain-breasted ground dove (Columbina minuta) which are about the same size as a house sparrow, weighing a little above 22 g (0.78 oz).[44][61][62] The dwarf fruit dove, which may measure as little as 13 cm (5.1 in) long, has a marginally smaller total length than any other species from this family.[44]

- Diversity of Pigeons and Doves

- The Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) is often stated to be the dodo’s closest living relative.

- Snow pigeon (Columba leuconota) in Sela, Arunachal Pradesh

- The stock dove (Columba oenas) of Europe is a typical member of the Columbinae.

- The common wood pigeon (Columba palumbus) is common throughout Europe. This one is eating Cotoneaster frigidus berries.

- The common ground dove (Columbina passerina) is one of the smallest species in the family.

- Nuku Hiva/Marquesan imperial pigeon (Ducula galeata)

- The Victoria crowned pigeon (Goura victoria) is one of the largest extant pigeons.

- The blue-headed quail-dove (Starnoenas cyanocephala) of Cuba is a relictual species with no close relatives.

- A red-eyed dove (Streptopelia semitorquata) on the Zambezi in Zimbabwe

Distribution and habitat

Pigeons and doves are distributed everywhere on Earth, having adapted to most terrestrial habitats available on the planet, except for the driest areas of the Sahara Desert, Antarctica and its surrounding islands, and the high Arctic.[50] They have colonised most of the world’s oceanic islands, reaching eastern Polynesia and the Chatham Islands in the Pacific, Mauritius, the Seychelles and Réunion in the Indian Ocean, and the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean.

Columbid species may be arboreal, terrestrial, or semi-terrestrial. They inhabit savanna, grassland, shrubland, desert, temperate woodland and forest, tropical rainforests, mangrove forest, and even the barren sands and gravels of atolls.[63]

Some species have large natural ranges. The eared dove ranges across the entirety of South America from Colombia to Tierra del Fuego,[64] the Eurasian collared dove has a massive (if discontinuous) distribution from Britain across Europe, the Middle East, India, Pakistan and China,[65] and the laughing dove across most of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as India, Pakistan, and the Middle East.[66]

When including human-mediated introductions, the largest range of any species is that of the rock dove, also known as the common pigeon.[67] This species had a large natural distribution from Britain and Ireland to northern Africa, across Europe, Arabia, Central Asia, India, the Himalayas and up into China and Mongolia.[67] The range of the species increased dramatically upon domestication, as the species went feral in cities around the world.[67] The common pigeon is currently resident across most of North America, and has established itself in cities and urban areas in South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.[67] A 2020 study found that the east coast of the United States includes two pigeon genetic megacities, in New York and Boston, and observes that the birds do not mix together.[68]

As well as the rock dove, several other species of pigeon have become established outside of their natural range after escaping captivity, and other species have increased their natural ranges due to habitat changes caused by human activity.[44]

Other species of Columbidae have tiny, restricted distributions, usually seen on small islands, such as the whistling dove, which is endemic to the tiny Kadavu Island in Fiji,[69] the Caroline ground dove, restricted to two islands, Truk and Pohnpei in the Caroline Islands,[70] and the Grenada dove, which is only found on the island of Grenada in the Caribbean.[71]

Some continental species also have tiny distributions, such as the black-banded fruit dove, which is restricted to a small area of the Arnhem Land of Australia,[72] the Somali pigeon, found only in a tiny area of northern Somalia,[73] and Moreno’s ground dove, endemic to the area around Salta and Tucuman in northern Argentina.[44]

Behaviour

Feeding

Seeds and fruit form the major component of the diets of pigeons and doves,[50][74] and the family can be loosely divided between seed-eating (granivorous) species, and fruit-and-mast-eating (frugivorous) species, though many species consume both.[75]

The granivorous species typically feed on seed found on the ground, whereas the frugivorous species are more arboreal, tending to feed in trees.[75] The morphological adaptations used to distinguish between the two groups include granivores tending to having thick walls in their gizzards, intestines, and esophagi, with the frugivores evolved with thin walls,[50] and the fruit-eating species have short intestines, as opposed to the seed eaters having longer intestines.[76] Frugivores are capable of clinging to branches and even hang upside down to reach fruit.[44][75]

In addition to fruit and seeds, a number of other food items are taken by many species. Some, particularly the ground doves and quail-doves, eat a large number of prey items such as insects and worms.[75] One species, the atoll fruit dove, is specialised in taking insect and reptile prey.[75] Snails, moths, and other insects are taken by white-crowned pigeons, orange fruit doves, and ruddy ground doves.[44] Flowers are also taken by some species.[4]

Urban feral pigeons, descendants of domestic rock doves (Columbia livia), reside in urban environments, disturbing their natural feeding habits. They depend on human activities and interactions to obtain food, causing them to forage for spilled food or food provided by humans.[77]

Reproduction

Doves and pigeons build relatively flimsy nests, often using sticks, other vegetable matter, and other debris, which may be placed on trees, on rocky ledges, or on the ground, depending on species. The female may either build the nest, with material gathered by the male, or the male builds the nest by himself. A few species nest colonially, others nest in aggregation.[4]

Most lay a clutch of one or (usually) two white eggs at a time which take 11-30 days to hatch (larger species have longer incubation times). Both parents care for the young; unlike most birds, both sexes of doves and pigeons produce “crop milk” to feed their young. This fluid is secreted by a sloughing of epithelial cells from the lining of the crop.[4]

Unfledged baby doves and pigeons are called squabs and are generally able to fly by five weeks old. These fledglings, with their immature squeaking voices, are called squeakers once they are weaned,[78] and leave the nest after 25–32 days.

Status and conservation

While many species of pigeons and doves have benefited from human activities and have increased their ranges, many other species have declined in numbers and some have become threatened or even succumbed to extinction.[79] Among the ten species to have become extinct since 1600 (the conventional date for estimating modern extinctions) are two of the most famous extinct species, the dodo and the passenger pigeon.[79][4]

The passenger pigeon was exceptional for a number of reasons. In modern times, it is the only pigeon species that was not an island species to have become extinct[79] even though it was once the most numerous species of bird on Earth.[citation needed] Its former numbers are difficult to estimate, but one ornithologist, Alexander Wilson, estimated one flock he observed contained over two billion birds.[80] The decline of the species was abrupt; in 1871, a breeding colony was estimated to contain over a hundred million birds, yet the last individual in the species was dead by 1914.[81] Although habitat loss was a contributing factor, the species is thought to have been massively over-hunted, being used as food for slaves and, later, the poor, in the United States throughout the 19th century.[citation needed]

The dodo, and its extinction, was more typical of the extinctions of pigeons in general. Like many species that colonise remote islands with few predators, it lost much of its predator avoidance behaviour, along with its ability to fly.[82] The arrival of people, along with a suite of other introduced species such as rats, pigs, and cats, quickly spelled the end for this species and many other island species that have become extinct.[82]

118 columbid species are at risk (34% of the total), with 48 species NT, 40 VU, 18 EN, 11 CR, and 1 EW.[4] Most of these are tropical and live on islands. All of the species are threatened by introduced predators, habitat loss, hunting, or a combination of these factors.[82] In some cases, they may be extinct in the wild, as is the Socorro dove of Socorro Island, Mexico, last seen in the wild in 1972, driven to extinction by habitat loss and introduced feral cats.[83] In some areas, a lack of knowledge means the true status of a species is unknown (DD); the Negros fruit dove has not been seen since 1953,[84] and may or may not be extinct, and the Polynesian ground dove is classified as critically endangered, as whether it survives or not on remote islands in the far west of the Pacific Ocean is unknown.[85]

Various conservation techniques are employed to prevent these extinctions, including laws and regulations to control hunting pressure, the establishment of protected areas to prevent further habitat loss, the establishment of captive populations for reintroduction back into the wild (ex situ conservation), and the translocation of individuals to suitable habitats to create additional populations.[82][86]

Domestication

Main article: Domestic pigeon

The domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica) is a descendant of the rock dove (Columba livia) that underwent domestication, with studies suggesting domestication as early as 10 thousand years ago. Domestic pigeons have long been a part of human culture; doves were important symbols of the goddesses Innana, Asherah, and Aphrodite, and revered by the early Christian, Islamic and Jewish religions. Domestication of pigeons led to significant use of homing pigeons for communication, including war pigeons, such as the 32 pigeons who were awarded the Dickin Medal for “brave service” to their country, in World War II.

The ringneck dove is a smaller species of domestic columbid that was kept as a source of food. As a result of selection for tame individuals who would not escape their cages, they lack a survival instinct and cannot survive release.[87]